As a continuation of the previous article, this would broaden our understanding of how the British colonial system changed the way we governed ourselves, moving us further from the traditional systems that once worked for us. The 1914 amalgamation, a decision made by the colonial powers and not the people, marked the start of a new era where control became more centralized and local leadership weakened. In this section, we will explore how Western-style elections replaced traditional selection processes, widening the gap between rulers and the people.

To me, the British made a fundamental error. You see, after destroying our institutions which were labelled hedonistic and barbaric in their standards, they had to teach us their ‘civilized ways’ in their own language. We learnt and learnt fast. Nigeria was only a microcosm in their vast colonial empire. The administration of this empire was proving to be a daunting and a most expensive task. Over the centuries they had lost America and Canada. India’s independence followed in 1947, Malasia in 1957. More countries in Asia and Africa were becoming restive, turning their languages and cultures against the occupiers. The educated Nigerian elites listened to the cries of their elders at home and took up the fight for independence as far as Westminster Halls of power. The colonialists caved in, pretending to do so reluctantly, but were truly glad to take their exits. You see, the British were beginning to bleed financially and, in some cases, militarily too. That was why they were unable to strengthen the institutions they left us; they ran out of time. It was clear they did not intend to leave so soon because we were ill-prepared to faithfully execute the demands of those civil institutions, with special emphasis on governance.

If we had to govern ourselves, we would need political parties, an alien phenomenon in our social life. So, the British told us. We were used to age grade groupings, traditional social associations, traditional religious groupings, and traditional medical practicing groups. But political groups, what were those? The more our people learnt about them, the more they realized that this new phrase held so much excitement, apprehension, fear, and uncertainty for our future. Largely, the colonialists had destroyed the sanctity of our Kings and Obas in the governance of the people. Never mind that the colonialists were protecting their kings and queens. However, in their excitement, the people did not completely cast away their Obas and Kings. And these erstwhile institutions of power now confined to ‘Traditional Rulers and Royal Fathers” demanded a voice in the new, emerging political structure.

It is important to note that while we practiced our natural form of administration in the pre-colonial empires, we had acceptable ways of cautioning an offending Oba/King, or in the extreme, removing a recalcitrant one. All the way down to the elders of the clans, these can be brought to book too. When an elder committed an infraction worthy of reprimand, the community would boycott all meetings with him until he apologized to the people and the gods, or he recanted whatever infraction he committed. How should we deal with the new phenomenon of political parties? How would we communicate with them? No one had a clue.

As far back as 1923, political parties started making their appearance in our emerging political landscape. The first was the Nigerian National Democratic Party (NNDP). Then came the Nigerian Youth Movement (NYM) and the National Council for Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC). Later, the Action Group (AG) and the Northern Peoples’ Congress were founded. The NNDP was a voice for the educated elite, pushing for greater representation of Nigerians in the colonial government. But as time went on and the call for independence grew louder, these other political parties emerged, each representing different regions and interests to add their voices to the demands of self-governance and then some. The colonialists encouraged these for it served their modus operandi of governance, divide and rule. Behind the scenes though, they encouraged and fanned the flames of ethnic divisions.

It is important to note that while some of the political parties tried to have a national outlook if only just in name and membership composition. The rest did not hide their regional or sectional interests and the Northern Peoples’ Congress definitively made it clear whose interests it came out to promote. This was not overtly concerning because for one, pre-amalgamation we only looked out for our individual regional interests based on the age-old empires. Secondly, Nigeria’s independence was delayed because the northern region was not ready with infrastructure and human resources required to run a quasi-autonomous government before 1960. Therefore, when they were ready, they emerged with NPC. What is important to note is that each of these parties had its own vision of what Nigeria should become. There was neither any organic conversation nor one driven by the exigencies of the period to coalesce their interests into a single national mantra for building a united, strong, and prosperous Country.

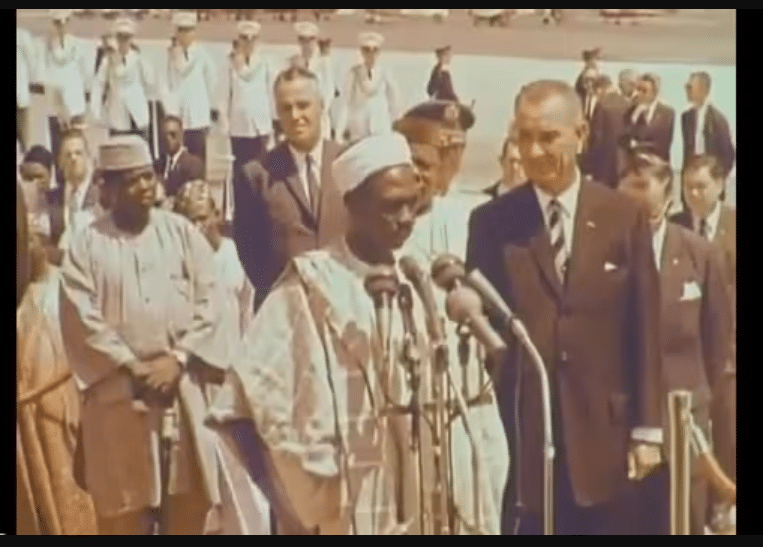

The clamor for independence reached its peak in the 1950s, and negotiations with the British intensified. The colonial government, recognizing the inevitability of change, began to introduce reforms that allowed for greater Nigerian participation in governance. Elections were held, and regional governments were established, giving us a taste of what self-rule could be like. However, these elections were not without their challenges.

TO BE CONTINUED……………