As a continuation of last week, where we discussed the regional and sectional interests that shaped Nigeria’s political parties in the pre-independence era, the growing complexities of these divisions became even more pronounced as the country inched closer to self-governance.

The first major elections took place in 1951, as part of the process of decolonization. We were filled with hope and anticipation, believing that this was the beginning of our journey towards true independence. But the elections did not unfold as we had hoped. The process was marred by confusion and controversy. The system used was complex, involving both direct and indirect elections, which led to disputes over the results. Political alliances shifted rapidly, and the competition between the parties became intense. It was clear that we were still grappling with the complexities of this new political landscape.

Despite the setbacks, the momentum for independence was unstoppable. The British, facing growing pressure from within and from the international community, began to set the stage for a transfer of power. But the road to independence was not smooth. The regional divisions that had emerged during the elections highlighted the deep ethnic and religious differences within Nigeria. These divisions would continue to shape our political landscape, even as we moved closer to independence.

The 1959 general elections, held as a prelude to independence, were meant to be a final step in the transition from colonial rule to self-governance. However, the election was fraught with tension and mistrust. The major political parties—NCNC, AG, and NPC—vied for control of the central government, each determined to secure their region’s interests. The outcome of the election was a coalition government, as no single party could secure a majority. This compromise reflected the complex and diverse nature of our nation, but it also underscored the challenges we would face in building a unified Nigeria. Our political leaders and the Council of Chiefs should have seen a coalition government for what it truly represents in Nigeria; that no one region can go it alone. Rather, and so unfortunately it would turn out down the years, the post-colonial leaders saw politics as a zero-sum game.

Post independence, it quickly became clear that the politicians had no understanding whatsoever of how to politick, especially in a multi-ethnically diverse country as what we were left to manage by the clueless colonialists. Despite the vision of the National Anthem, the politicians did not see our diversity as strength, nor as a means to forge a united country with one purpose; that we needed to create a strong vibrant nation where all peoples are equal and individual rights are respected. Rather than see our diverse regional needs as rights that should be accepted, respected, and accommodated in equal measures in the process of nation building, the politicians treated the rights of the dominant regional political power as supreme and equal to none other. The wishes of the dominant political party were far game to be imposed on other regions. With this mind set it was so natural for elections to devolve into fratricidal combats that must be won at any cost. Loyalty to party was seen at first to mean loyalty to regional power that has no accommodation to the interests of the opposition.

The challenges of building a unified country out of a patchwork of diverse regions, ethnicities, and religions were becoming immense with each passing day. It wasn’t long before the fragile democracy we had fought so hard to establish began to show signs of strain.

The first cracks appeared in the early 1960s well before Independence Day on October 1, 1960, aided by the colonialists who in their wisdom apportioned a higher population figure to a region that was 60% arid. And practically ill-equipped to support such a population. The final straw came with the highly contentious 1964 federal elections, which were marred by widespread violence, voter intimidation, and allegations of rigging. The election results were contested, leading to a deepening crisis that the civilian government had no appetite to resolve. Political parties that showed a semblance of national spread by winning seats across regional divides lost those victorious party members to the entrenched regional parties overnight. The mantra was more like, “to your regional tents oh politicians” to resolve.

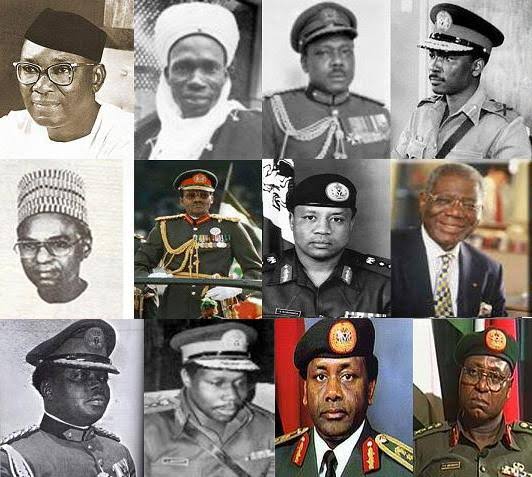

We all are living witnesses to history that unfolded in 1965 to date. The military stepped in hoping to sanitize the appalling situation that had descended on the nation. And so began the cycle of coups and civilian experiments at governance that lasted from 1966 to 1999, 34 years. In that period of 3 and half decades, we fought a civil war that extinguished the lives of over 3million of our people, had seven successful coups that assumed power and governance, had two known failed coups, 2 botched civil administrations that failed to function for the people. The totality of that period did not produce the governance that Nigerians wanted.