As I embark on writing the final chapter of my five-part series, “The Death of a Hero”, I am met

with a mix of emotions and reflections. The title itself has sparked a multitude of questions and

anxieties, and I must say that I am delighted by the curiosity it has generated. The inquiries and

concerns have provided me with a unique opportunity to pay tribute to the unsung heroes who

have inspired this series.

These heroes, unfortunately, remain nameless, faceless, and unidentified, stripped of their

nationality, gender, and race. All that remains of them are their skeletal remains, a haunting

reminder of the harsh conditions that they faced. It is likely that their bodies were ravaged by the

scorching sun, leaving behind only their bare bones as a testament to their existence. I can only

imagine that they, too, had attempted to cross the desert, driven by a sense of adventure and

determination, but ultimately succumbed to the unforgiving environment.

As I reflect on their story, I am struck by the realization that I have, in a sense, stood on their

shoulders. Their bravery and perseverance have paved the way for me, and I am humbled by the

thought of the sacrifices they made. It leads me to ponder the differences between their dreams

and mine, and what drove them to attempt the impossible. Were their aspirations similar to mine,

or were they driven by different motivations and desires?

In this final chapter, I aim to honor the memory of these heroes, who, despite their anonymity,

have left an inexcusable mark on my journey. Their story serves as a reminder that even in the

most challenging and inhospitable environments, there are those who dare to dream, to strive,

and to push beyond the boundaries of human endurance. As I bring this series to a close, I hope

to do justice to their memory, and to inspire others to draw strength from their example, just as I

have.

One thing I discovered while in Tamagasset is that I should not drink from a different cup from

intruders. I was taught to really identify with them by serving one person and using the same cup

and then serving myself before serving another person. This technique helped me, as a bond was

quickly established. Besides that, it helped to douse the atmosphere that was already very tense. It

also helped me to go into the next stage of communication by offering them money, some food

and water. I took time to explain what my mission was. I could not give them any paper because

it was dark.

They had asked me to put off my searchlight immediately when they came close to me. I then

offered them about 7000D, and the way they handled it obviously showed that it was not enough, so I had to give them another 3000D, gave them some of my food items, especially corned beef

and sardines and some water. They ignored me for a while and spoke among themselves in Arabic

for about 20-30 minutes. By this time, it was getting to about 5am, and I told them I was going to

make my breakfast, if they cared to join me. They said neither yes nor no, but I went ahead all the

same and made breakfast for five. The breakfast was made up of some custard, dry bread, some

sardines and chocolate. It was obvious to me that they enjoyed the meal so well that another round

of argument/conversation ensued among them for fifteen minutes. At the end of this, they got up

reluctantly, mounted their horses, and left. I heaved a sigh of relief and looked at my time. It was

5.30am. I quickly packed my tent and belongings, entered my jeep and started off for El-Meniaa,

leaving a swirl of dust behind me in my haste to put a lasting distance between my desert visitors

and me.

Before reaching El-Meniaa, somewhere after In-Salah on the outskirts of El-Meniaa, I encountered

a roadblock mounted by the police, the gendarmes and the military. Having driven for 10 hours,

covering 620km without stopping, because of my encounter with the bandits, I was dog-tired, and

the last thing I wanted at that time was another roadblock search, but I was in for it this time. The

three groups checked me separately, each repeating the activity of the other. At this point, El

Meniaa was only 10km away, and I was instructed to go to the Gendarme headquarters inside El

Meniaa town, not only to register my person, but also to discontinue my voyage until I had received

clearance from the Commandant. I asked questions and was piloted to the Gendarme headquarters,

where I learnt that the Commandant had gone home before my arrival. “Oh, dear,” I muttered. “I

have to sort this out this night, since I intend to continue on my journey the following morning.”

One of the gendarmes was kind enough to take me to the Commandant’s house that night. The

Commandant was a very nice person, who told me that they knew about me, but he was not going

to clear me because of reports they had been receiving regarding the activities of some bandits on

that route. He said they had instructions not to allow anybody to take the route until they had

thoroughly investigated the information on the activities of the bandits who had robbed and killed

some security men on patrol in the desert some days back. Since the bandits I had met had been

very nice to me, at least for sparing my life, I kept the encounter secret from the commandant for

I reasoned that this might delay me and make me part of the investigation.

I did ask him how long it might take me to obtain the clearance, and his answer was indefinite. He

then asked me to report at the headquarters the following day, but would personally advise that I

discontinued the trip, at least for now until we speak again the following day. This was a

devastating blow on my good progress so far and I showed it to all. They could not care less for

my plight. The gendarmes took me back to a petrol station where I met some trucks that were

equally stopped from traveling, though they were on a different route from mine.

The petrol station became a motor garage cum camping ground for us all. I camped there, and this

time I decided not to cook, but to buy my food- first to save my food, especially since I had given

away lots of food to the bandit; and secondly to avail myself of the opportunity offered by the

emergency restaurant all around the petrol station.

My stay there was not all that pleasing, because I felt that my mission was being disrupted, but on

learning that some of the trucks had been packed there for days waiting for clearance, I took solace

in my freshness in the stranded community. I spent the night in my car, as there was no need for

the tent. The following morning, I seized the opportunity of camping at the petrol station to service

my car. I filled up my fuel tank and reservoir and then went to the Gendarme headquarters with

others to seek clearance. Typical of government offices, it took a whole working day to get this

clearance, and late in the evening at about 5pm, we were finally given the signal to carry on with

our trips. With the night fast approaching, I decided to spend the rest of that day and night at El

Meniaa. The following day at 5am, the cold weather notwithstanding, activities at the petrol station

were in frenzy, as many travelers were ready to leave. I quickly put a call through to my wife, and

at 6.30am, I resumed driving.

Four hours later, I arrived in Ghardiadia. Here, the natural beauty of the environment struck me. It

was one of the most beautiful places I have ever been to. Ghardiadia is blessed with beautiful

mountains and wonderfully adorned valleys. It also has lots of human and vehicular traffic, not the

type that keeps one on the road for hours though, but the type that assures one that the people have

good living standards. There were also many visible functioning industries and infrastructure. In

fact, I never knew or could ever believe that a place like that existed in the middle of the desert.

Although my route did not take me through the center of the town, what I was able to see from the

hilly side allowed for some exceptional photographs given my vantage point.

From this place, I began to encounter more policemen and gendarmes than I did in the past. There

was a paved road, and being real close to civilization now, my car became a kind of entertainment

to them, and from that point, I was stopped many times at the checkpoints for chats about my

voyage, rather than the usual checks. Funny enough, it was at one of those checkpoints that I got

to know about the Kaduna riot; a religious disturbance that had taken place in Nigeria a few weeks

back. Driving farther down into the desert with Ghardiadia now 200km behind, I came face to face

with death a second time. This time I encountered heavily armed military men who turned out to

be fundamentalists. They stopped me, did not bother to say anything to me, and just waved

instructions to me to follow them. I drove behind them, and on getting to a place that could be

described as a secret settlement; I was subjected to a frightening interrogation.

In all fairness, they were neither hostile nor friendly. They were plain professionals. Their manner

of approach revealed their open curiosity. They enlightened me as to their identity and mission,

and then queried my knowledge of their existence. I answered in the affirmative and even told

them about their annulled election many years back, which might have triggered their differences.

They later sought my opinion on their activities, but on this, I maintained my distant relationship

with politics, but explained that I very much appreciate the problems in their country and praised

their efforts in seeing the sanitization of their system. Before concluding this session, which lasted

for about six hours, I had drunk about three to four cups of tea with them.

The tea, which they offered from their stock, they said, was homegrown. It had a unique taste,

something different from the taste of regular tea, and I was tempted to request some for the road.

This thought was the least of my problems. I was carried away by the joy of being set free and the

uncertainties surrounding the remaining part of the voyage made me indifferent to everything other than driving away as fast as I could into the distance. Two hours into the highway, I encountered

yet another set of heavily armed men in two vehicles. I was getting quite irritated at this encore

with the military, bandits, and gendarmes. This time, it was the Algerian Army. From the very first

question they asked, it was obvious that they had information of my encounter with the Islamic

fundamentalists. My suspicion was that they had a spy among the fundamentalists. They, too, were

nice during my encounter with them. They wanted to know if I was intimidated into showing some

kind of support to their cause. Not wanting to be a coward, I praised the good side of the

fundamentalists. I told them that they were kind, polite, courteous, and so on.

I went on to explain to them that I informed the fundamentalists that I was an innocent traveler,

who does not have anything to do with the differences existing between them and the Government

of Algeria, and being satisfied, they allowed me to go. At this stage, a cordial relationship had

developed between the government army and myself, and one of them even jokingly asked if I

would like to have tea with them. This I declined and pleaded with them to let me go, as I still had

a very long stretch to cover. This request almost got me into trouble as one of them got angry and

queried my sudden realization that my journey was not done yet, while I spent five hours with the

fundamentalists. From that point on, I took the posture of a lamb about to be slain and kept my

mouth shut as they began a fresh round of search on the car and myself. They really took their time

in doing that, and having satisfied themselves, I was allowed to go eventually.

If I had not survived my perilous journey through the desert, the question on everyone’s mind

would have been: “What drove him to venture into such a treacherous terrain, and what was he

searching for that was worth risking his life?” The tragic outcome would have been met with shock

and sadness, and the news of my demise would have been splashed across the headlines as “The

Death of a Hero”, a poignant reminder of the high cost of adventure and exploration. The thought

of my body lying alone in the vast expanse of the desert, with no one to claim it or bring it back

home, is a haunting one, and it is a sobering reminder of the risks that I took and the fragility of

life.

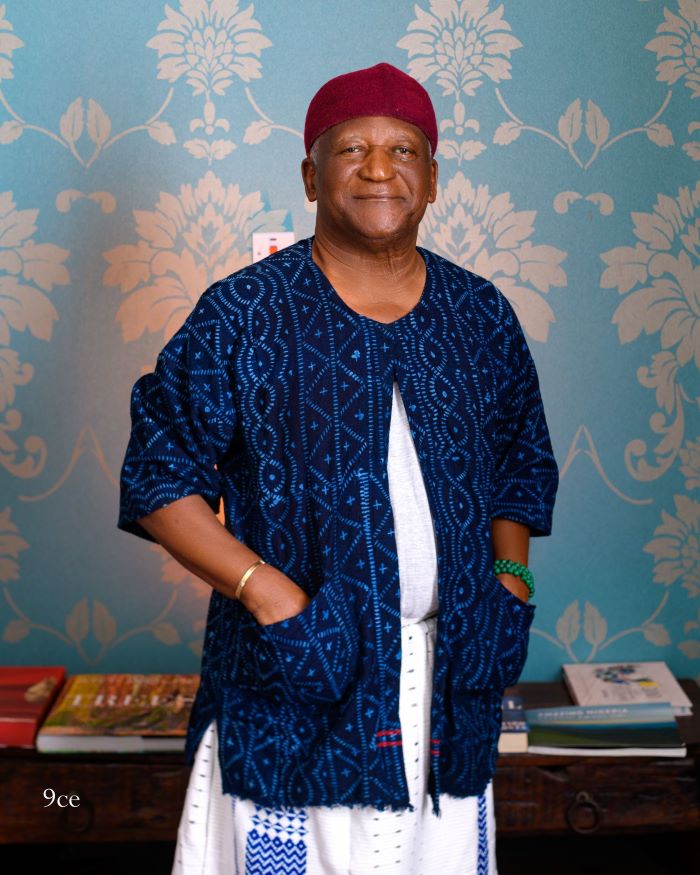

As I look back on my life, I realize that the title of Nnaobodo is not just a recognition of my age

or status, but also an attestation to my experiences and the lessons that I have learned along the

way. It is a cue that leadership is not just about age or position, but about the wisdom, courage,

and resilience that one has developed over the years.