One evening, during a recent festive period, which I had spent in my hometown, I decided to visit a friend in the neighbouring town and, as was my usual custom in my hometown, I drove my eighty-year self across towns. You see, all over my state, I am known as the Desert Warrior, in fact, in some instance, I am introduced as such. On this occasion, as I drove to my destination, I came upon a police checkpoint, where four policemen were stationed. As soon as they noticed me, they began chanting, “Desert Warrior, your boys are here.” Since it was the festive period, I chose to pull over and, as I did, one of them ran over and I gave him N2,000 for all of them. Immediately he collected the two N1,000 notes, he quickly put one in his pocket and held up the other shouting to his colleagues that the Desert Warrior had given them N1,000. I was already pulling away at this point and was tempted to reverse to challenge him but, you see, he was carrying a gun and I didn’t want to be the victim of an “accidental discharge,” a common mishap with our men in uniform. My encounter with the policemen in my hometown is not an exclusive experience, which only goes to show just how corrupt the average policeman is, even to his mates, regardless of tribe, education or religion. I then have to ask, how far down can we go before something is done to check the level of policing in our country Nigeria?

How do we expect them to safeguard life and property, if they are not sufficiently trained and equipped to carry out their functions? What hope do we have of them solving complicated cases when a simple robbery barely ever gets solved? Who is the policeman that would go undercover today to solve a case? How many cases of corruption have the police, EFCC or ICPC successfully prosecuted? How many people have our courts and judges put away for corruption? We live as if we make our own laws as we journey through life. We still see laws as those produced by the colonial masters to punish us. Hence, we must beg and bribe our way through the law courts, when we cannot bully our way through.

Nigeria is a country of laws. We have the penchant to make good and well-researched laws, a bit borrowed from the British, a bit from the USA, especially its Constitution. A good number of our laws came from the military, who structured them in such a way to ensure their indefinite participation in the affairs of the nation. In the main, all laws have been made to protect the citizenry, big or small, young and old, poor or rich.

If that is the case, one may ask: how come we are perceived as one of the most lawless nations of the world and fantastically corrupt?

I have travelled and lived in most parts of Nigeria and I have observed that those that make the laws, those that wrote the Constitution and made the decrees, and those whose duty it is to enforce the laws are the same people that mostly and wantonly flout the laws. The consequences of this include the fact that Nigerians respect lawmakers but not the laws; they fear the law enforcement agencies but pay very little regard to the laws they are trying to enforce. Naturally, Nigerians are easy to govern but lawless because of the impunity of the law-breakers in high places. If we were really law-abiding and the enforcers could do their jobs with integrity, if the leaders could only exhibit a modicum of good governance, there would be very little talk about restructuring, sovereign national conference, or state policing. Rather, we would engage ourselves in such discourse as our ability, sincerity of purpose and transparency in modifying or changing obsolete laws with the dictates of a dynamic society. We would advocate progressive changes with a good heart and not remain mired in archaic and feudal laws. We should cease politicising our intents and dump the notion of North/South dichotomy when we embark on any project that is for the common good. Let it be known that the killers in our judicial process are nepotism, sectional bias, cronyism, and lies.

If we must continue to see Nigeria as one, we must begin to rise above having an Igbo leader for the Igbo, a Yoruba leader for the Yoruba, and a northern leader for the Hausa/Fulani. How and when can a good leader emerge so that we can face the very serious security problems facing us, tackle our underperforming economy, revamp our educational sector, which is the driver of the human resource for our development as a nation? Who will lead us to understand that there can be no industrial development without a solid agricultural base and a fully developed electric power infrastructure? Who will be the leader that would encourage research into sustainable living, or that which can put us in space? Who is the leader that would actually interview a prospective minister for the portfolio that will be designated to him or her? You may ponder the relevance of all these questions to our topical issue today. But these questions must produce the right answers from us, our leaders, if we must not remain as a failed state. We cannot do the right things sought by the answers to these questions if corruption is left to thrive. And thrive it will, if the police continue to look the other way or participate in it. One last question: has any one looked at the real costs in monetary terms of the effect of corruption on Nigeria? I may make bold to say the cost is in excess of 250 per cent of our GDP.

As a young man, I listened to talks about the roles the Nigerian law enforcement agencies played in the various peace keeping deployments around the world in the middle to late 20th Century. We were told that, if the performances of the countries of the world were to be scored or ranked, Nigeria’s scorecard would be among the best 10 in the world. Just a few years ago, there was a gathering of police officers from many countries for some special police training programme in Houston, USA. A Nigerian police officer was the best all-round student and was given a citation at the graduation ceremony. He was hosted by Nigerians in Houston at an event where I was present, having changed my travel plans on the news of his achievements. I was proud to associate with him and to witness his moment of glory. For me, it was doubly a proud day because the officer was a DPO that was then serving in my home town.

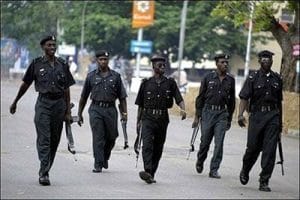

Today, with all due respect, our police are a pitiable sight. A good number of them are left on the various highways where they beg for money with their guns in tow, harassing and intimidating hapless motorists. Their police stations and barracks are places you do not want to be seen going into or exiting. I hear that the upkeep for their stations is sometimes funded in part by the tolls they collect on the highways and the bail monies they collect from victims of their frequent and sometimes frivolous arrests from the communities they are meant to protect in the first place. I also hear that they are supposed to replace their uniforms from their meager resources, which explains why some of them who are not corruptly resourceful appear in tattered uniforms.

In the first quarter of this year, a campaign started on social media raising awareness to the unlawful, brutal, and torturous behaviour inflicted on young citizens of this nation by the very organisation set up to protect them. The #ENDSARS campaign raised a lot of concerns and a lot of young, affected citizens gladly shared their stories in hopes that the Federal Government would help bring the actions of SARS to a complete stop or at least under control. There were stories of SARS operatives harassing young men for flimsy reasons, without going through the proper protocol and without substantial evidence against these young men, they were arrested, bound and taken to SARS headquarters or nearby ATMs for extortion.  SARS which stands for Special Anti-Robbery Squad was set up as an elite team to fight the criminal cases that were beyond the police force. Why is it that the same SARS operatives assigned to protect the citizens are the ones terrorizing them? As with most Nigerian civil campaign started online, the #ENDSARS flames fizzled out faster than it had started. I believe part of this was because the police force actively tried to put an end to any offline protest going on within the nation. The protesters soon realised that life is more important than protesting a cause that was likely not going to be fulfilled.

SARS which stands for Special Anti-Robbery Squad was set up as an elite team to fight the criminal cases that were beyond the police force. Why is it that the same SARS operatives assigned to protect the citizens are the ones terrorizing them? As with most Nigerian civil campaign started online, the #ENDSARS flames fizzled out faster than it had started. I believe part of this was because the police force actively tried to put an end to any offline protest going on within the nation. The protesters soon realised that life is more important than protesting a cause that was likely not going to be fulfilled.

How did the police get to this stage? In the second half of the ’80s, DSP Alozie Ogugbuaja in an extraordinary treatise decrying the poor funding of police institutions informed a coup-weary nation that it was in the over-arching interest of the Nigerian Army to keep the police down as an ineffective force. Ordinarily, a well-trained and well-funded police force should be able to detect a coup in the making, prevent a coup, or investigate a coup. Whether by commission or omission, this poor funding of the police has continued to this day. Worse is the practice of embezzlement and fraud within the highest echelon of the institution, exacerbating an already precarious and dangerous position the police are in. The consequence is that the police is now ill-equipped to execute its primary mandate in any manner or form. Our police cannot even mount the simplest of sting operations or infiltrate a gang in pursuit of law enforcement, or for the purpose of breaking them up. Presently, it has been reported that over half of the police force is now engaged in personal and private security details for politicians, public servant, and the rich. Under such circumstances, it is little wonder that gangs and militias can form, fester and grow into major terrorist organisations like Boko Haram, separatist movements like MASSOB, tribal militias like OPC, Arewa Youths, MEND, etc.

The security challenges facing this nation are made worse by the porous borders and inadequate security that exist with our neighbours. Migrants from such countries like Cameroun, Niger, Chad, and the Republic of Benin, pour into Nigeria in their millions and do not return to their countries. This phenomenon bloats our population so much so that we cannot keep up with the census, but rather give estimates that are frequently being revised. This is bad for socio-economic planning. It is bad politics, and it breeds courtship with danger. A case in point is the migration of hostile Fulani herdsmen, some of whom are unauthorised aliens in the country. The actions of these marauders can pitch this nation into another civil war. These are civilians with arms carried in the open and our police look the other way. Incredible! This cannot happen in other ECOWAS countries. Any Nigerian caught in those countries without any valid immigration papers will be dumped in jail before he can say his name.

The sad irony is that most of these countries do not harbour Nigerians the way we accept their nationals. Here in the country, they can obtain Nigerian passport with ease but Nigerians who want to stay in those countries remain as aliens, if they are allowed to stay at all. These lax border controls put heavy pressure on our economic and social services, with the concomitant heating up of the polity. As I have said previously, more than a third of Nigerians have no fixed address. It is quite easy to get all these aliens out before they take over our country. Thirty-three percent of our population is close to 66 million. We cannot afford to be silent.

It is definitely important for us to get security right. This was a great article. Keep it up FADE!